"People think they know Frankenstein but what they often know is the manglings the novel has received in various film and TV adaptations."—illustrator John Coulthart

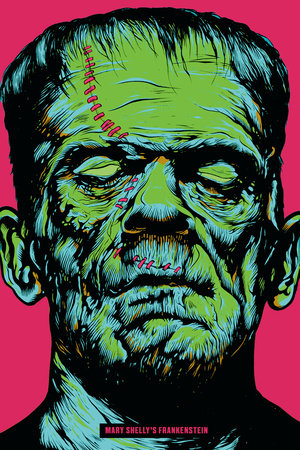

Frankenstein is one of the most famous novels in the world, but if you've never read it then your idea of the story is probably informed by this image:

The modern iconic representaion of Frankenstein's monster has two key features: he's dead and he's dumb.

Look at his corpse-green skin, his scars and stitches, his stroke-slumped face—he might be 'alive' thanks to mad science, but we all know really he's dead. He's zombie-plus.

And look at his block-like head, his drooping eyes, his dull mouth—no sign of light, curiosity, or intelligence. He's dumb as a rock. If you were to sum him up in a sound, this Frankenstein would be saying, "GUH..."

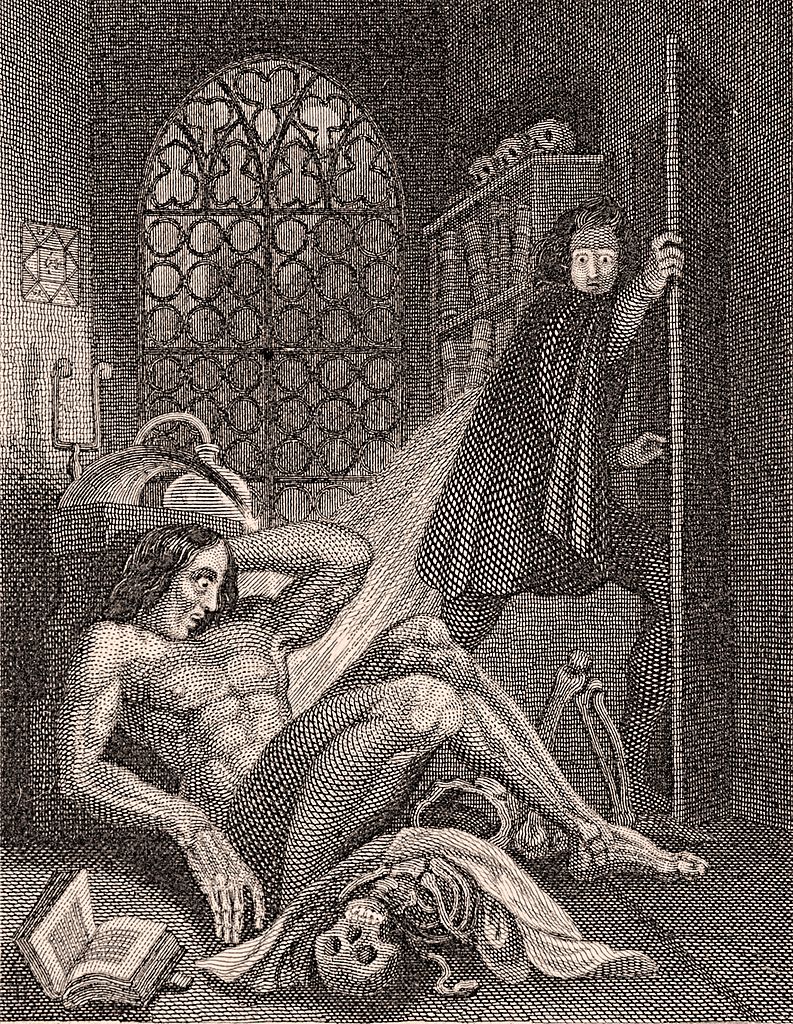

In contrast, the earliest art that came with the published novel was this etching, which tells a different story:

If you zoom in on the monster's face, the big blinking message is, "WTF!?"

Because unlike the shambling, grunting, walking dead cinematic version of the monster, the original creature is the opposite: he's hyper-self-aware, intelligent, articulate, emotional, and tortured by the idea that he is a reanimated corpse-collage with no-one to love him.

Frankenstein is a book about social and emotional upheaval

In the book, the creature isn't the only one freaking out. After all, it's a 19th century British gothic-romantic novel, so everyone's emotions are dialled up to 11.

One reason is that in those days people kept dying young. Mary Shelley's own mother died the month after she gave birth to Mary. When she started writing Frankenstein, Mary Shelley was 19 years old, and she had already had one child who had died. She would have three more children in the following years, only one of whom would survive. Her husband would die after the birth of that fourth child. And that's just scratching the surface—if you want more bodycount, just go read Mary Shelley's Wikipedia page.

So: death. In many societies, we cope with the idea of our own mortality through religion, which gives meaning to our death. But in 19th century Europe, people hit an inflection point in science where the rate of discovery about nature started to seriously challenge religion as a source of power and meaning.

You can see all these themes in Mary Shelley's account of the conversations, and subsequent nightmare, that gave rise to Frankenstein:

"Perhaps a corpse would be reanimated; galvanism had given token of such things... When I placed my head on my pillow... I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together; I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out... Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the creator of the world."

So in a nutshell, Frankenstein is about a group of characters, including one newly reanimanted corpse, having an emotional breakdown while grappling with questions about life, death, god, nature, science, and human society.

(It's also about the emotional impact of hiking in Switzerland, but that's a subject for a different lesson.)