You can do this in 8 hours

While there's a lot here, you can cover it relatively quickly.

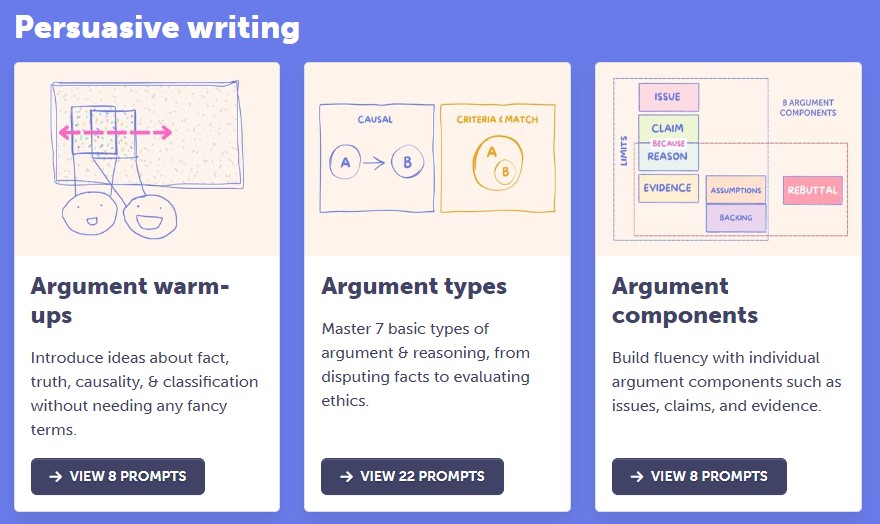

There are 7 argument types and 8 components.

If you think of each argument type and component as a 30-minute game, that's about 8 hours of gameplay to learn the framework.

If you played one game per week over 15 weeks you'd get through the whole framework in two terms, and you can integrate it with whatever unit content you're teaching.

Just follow the Argument prompt presets!