There's an aspect to connectors that we've been conveniently ignoring, which is 'coordination' vs. 'subordination'.

In case you missed the aside earlier this lesson, there's a level in between word groups and sentences called 'clauses'. Clauses are important for understanding coordination and subordination.

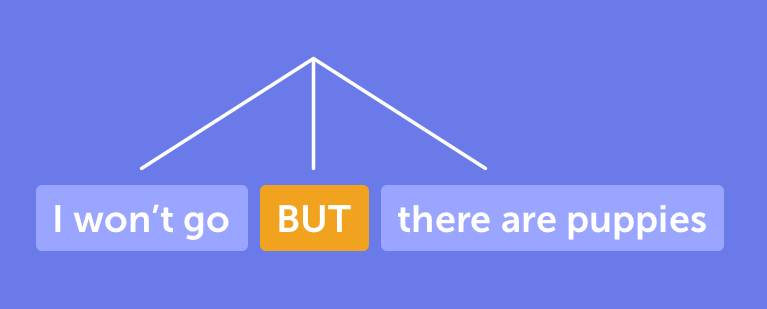

'Coordinating connectors' (such as 'and', 'but', 'or', 'yet', and a few others) are not part of either clause that they are connecting.

This is actually the strictly grammatical definition of 'compound sentence' that we alluded to earlier in this lesson—a sentence where the connector is not part of a clause.

Coordinating connectors must go in between two clauses.

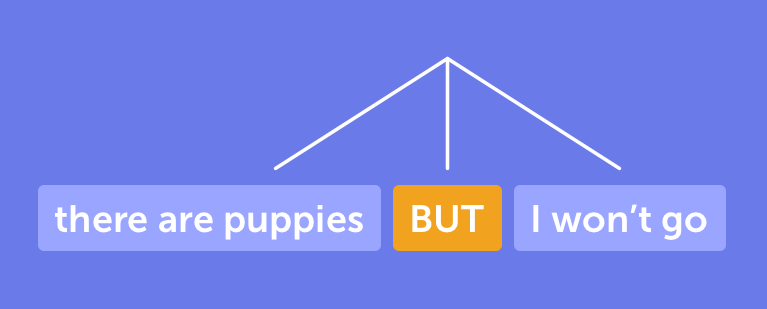

We can swap the clauses around like this:

and the sentence still makes sense (although the meaning might change).

But the connector can't move or you end up with gibberish:

(A quick note: this is known as a 'run-on sentence', because it's two sentences that just run into each other without anything to control the flow and intonation. They're difficult for readers to follow, so if you see any in your writing, try to fix them with full stops—"But I won't go. There are puppies."—or connectors—"But I won't go because there are puppies.")

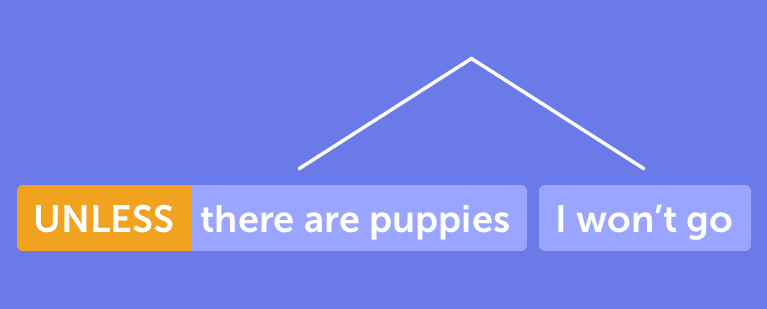

'Subordinating connectors' (like 'if', 'because', 'though', and many, many others) are actually part of the clause they introduce.

We can swap the clauses around like this, with no change in meaning:

The connector can move, but it has to take the rest of the clause it is attached to with it.

From a strict grammatical perspective, we would call sentences with subordinating connectors 'complex sentences'.

We talk more about subordination in the lesson on complex sentences. For this lesson, the important thing is to recognise that 'if' is a connector, it can appear in unusual places in the sentence, and that there are lots of other connectors that can do the same thing.

As for why 'if' clauses seem more likely to show up at the start of a sentence than other connectors, it's probably just a collective habit from when English required conditions to be constructed with 'if...then' (as in "if you climbed the dying jarrah trees down there towards the creek, then you could see the lights of the city").