In this specific scene, there's a good reason the narrator goes into omniscient mode: if they didn't, then the audience would not understand why the crane suddenly started working (body temperature activation) or why Alex could drive this crane at all (this model is designed to be especially easy and accurate).

But you can go even bigger

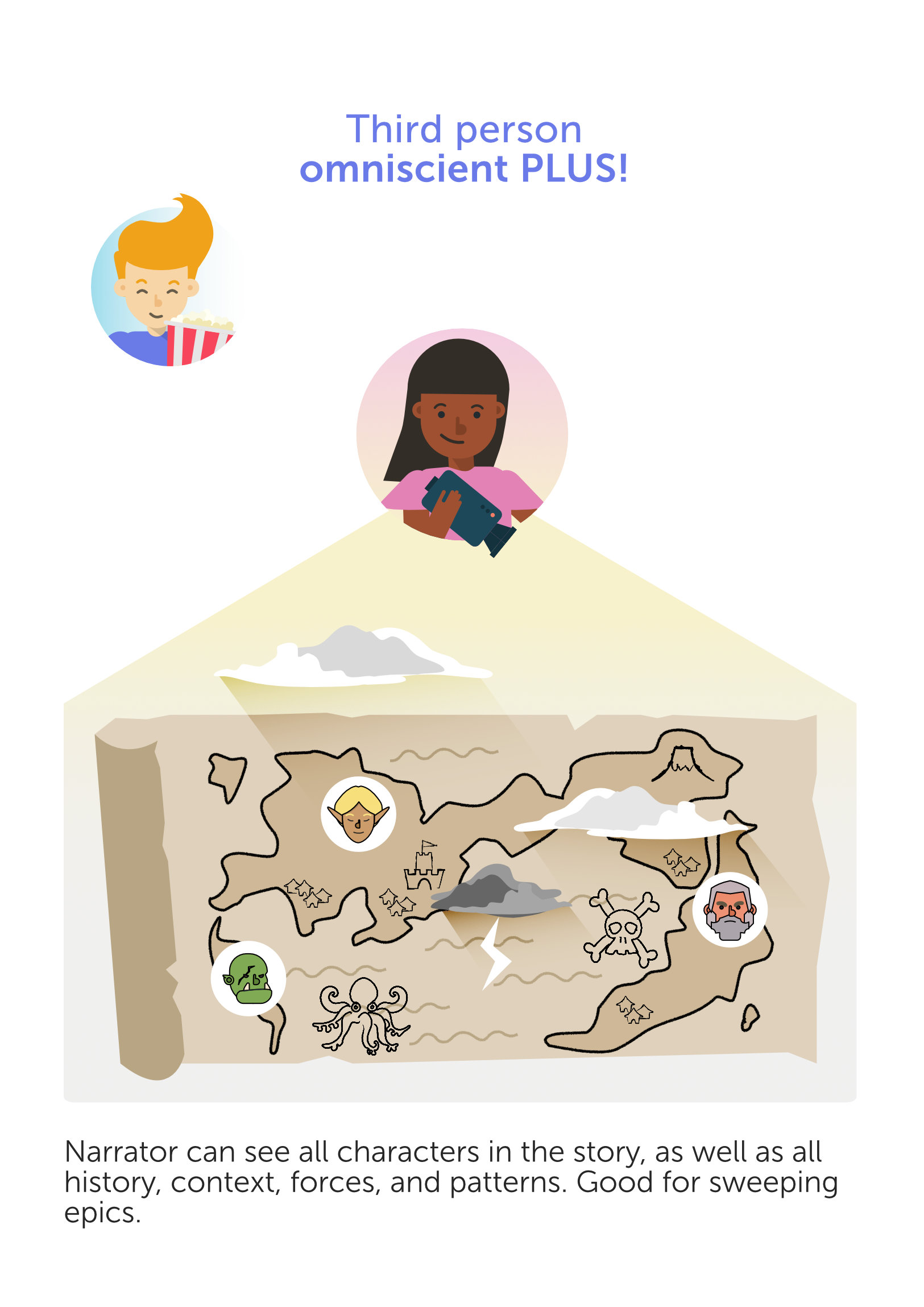

With 'godlike' omniscience, the narrator kind of floats above the story world and can describe not only characters, but also histories, industries, cultures, patterns, insights, themes, ideas—whatever they want.