A few weeks ago I suggested that one way to help struggling writers was to encourage them to write lists and fragments.

Since we had some more feedback from a teacher struggling with this issue, I thought I'd use this week's newsletter to build on this topic.

Fragments = raw material

By fragments, I mean descriptive details unlinked by verbs or any other connective words or phrases.

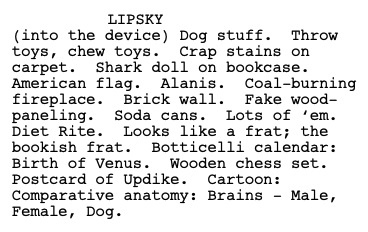

For example, there's a great scene near the end of the movie End of the Tour (based on the book, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, about going on a book tour with David Foster Wallace) in which journalist David Lipsky rips through Wallace's house with an audio recorder, quickly capturing details he notices in each room:

This kind of list-making is often the raw material of a writer's work.

From a teaching perspective, focusing on fragmentary details reduces the cognitive load for developing writers—and you can use that spare capacity to develop some underlying craft skills.

Here are some tips on how to approach that.

Skill 1: Scanning along axes

Previously, I talked about the skill of systematically scanning a stimulus image for ideas and I shared a game format that directs player attention along different axes:

- Look at the surface of the image and note obvious details

- Zoom in and capture hidden details

- Zoom out and imagine details beyond the edge of the frame

- Introduce details that deliberately break context

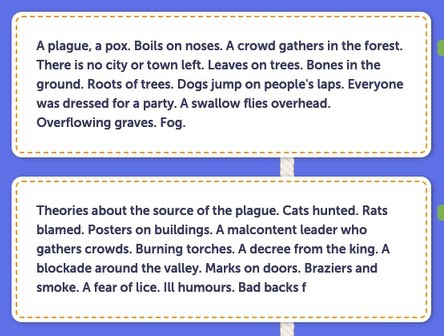

Here's another example of what that looks like in practice:

Skill 2: Brainstorming story elements

The above format trains students to direct their attention in space and time: zooming in and out, panning left and right, going back in time.

Another approach is to look for certain classes of detail based on text type. For example, brainstorming across four basic narrative elements:

- Characters

- Objects

- Places

- Events

Here's an example in which players brainstorm about Cuddles, the Flame Retardant Megabear:

The first approach teaches students how to scan an environment and engage with a stimulus; the second approach develops basic genre skills.

Students can get better at both of these skills

This might all sound trivially easy, but give it a try and you might find that students struggle!

It's often hard to keep players from jumping straight into dialogue and action, and stopping to observe closely can feel very weird.

But if you really focus on this, you can encourage students to become:

- more patient

- more observant

- more detailed in their description

- more tasteful in their selection of details.

And if you are playing a game with mixed-ability students, you can establish a practice whereby some students write fragments and details as a way to feed ideas to other players (who might read them during voting rounds and incorporate them in subsequent writing rounds).

This approach allows for differentiation while also developing genuine collaboration skills.

"It's not real writing?" Tell that to Dickens!

This might look like a cop-out, especially when working with older students, but sometimes excellent writing is barely more than a well-done list.

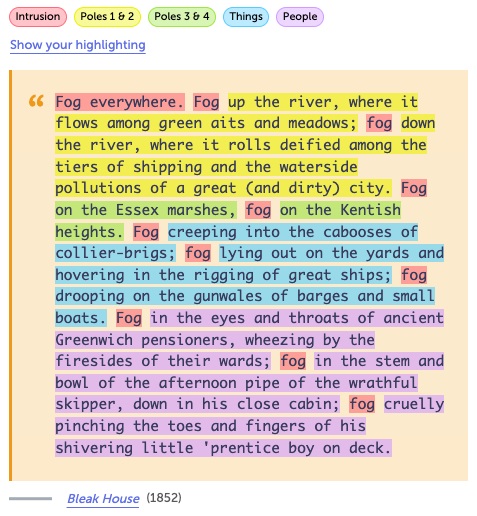

For example, we have a whole lesson in Writelike devoted to one of Dickens' most famous openings, his description of London fog in Bleak House:

One of the greatest passage in English literature, and it's a list of people, places, and objects, organised on north-south, east-west, big-small, old-young axes.

You can then move on to combining details

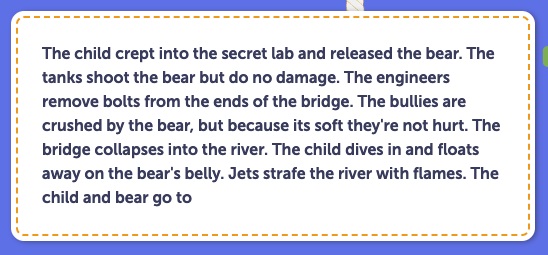

Once you have a pile of raw details, you can try connecting and combining them.

Combining is a topic in its own right, but briefly, I mean making elements interact in some way.

- In narrative and argument, this is about building relationships between details.

- Grammatically, this is where we make more use of verbs and connectives.

In both of the game formats described above, we'd typically use Round 5 to combine details in crazy, funny, surprising ways, whether or not they made sense, just to unleash some of the bottled-up energy created by gathering details:

If players can combine details in a way that creates some kind of meaning, it can feel like solving a jigsaw puzzle.

If you have any questions, comments, or criticism

Feel free to get in touch! I'd love to hear your thoughts.

If you want more details on the subject of details and fragments, check out Establishing the world in Teaching Narrative Writing with Frankenstories.