We've recently been collecting a lot of teacher feedback on Frankenstories and several teachers have mentioned the difficulties of supporting struggling writers in their classes.

Since I don't have any big feature or content announcements this week, I thought I'd offer a piece of advice in the context of Frankenstories.

That advice is simply: encourage students to write fragments and lists of details.

Fragments are the raw material of thought

All writing is about making a model of the world, and that model-making has three steps:

- Choose details

- Put those details into some kind of relationship

- Show what that relationship means

(In narrative, the relationship is usually cause & effect and the meaning is emotional. Argument expands to include categorical and principle-based relationships, and "meaning" comes from conclusions about reality or values.)

Everything rests on detail, and many people, not just struggling students, have trouble gathering enough detail to begin making connections and establishing meaning.

So it's worthwhile getting students to practice gathering details in different contexts—and those details are usually captured as fragments, not prose.

(The image above is a snippet from Sylvia Plath's journal, where she captures details of a winter landscape.)

More valuable real-world work is done with fragments than with prose

I don't know if this is next point is entirely true, but I think there's a case to be made.

Generally, school values prose. Students are rewarded for complete sentences with meaningful connectives.

Fragments, bullets, and other scraps of text may be valued in the research & brainstorming phases, but the "real" value is in the final essays & stories (maybe some presentations and media, but even those are expected to have underlying prose scripts).

But if you were to go into most workplaces, including some of the most language-rich environments, you'd find that 80% of the valuable work is embedded in fragments: it's in notes, post-its, comments, lists, diagrams, sketches.

Piles of raw material that are collated, sifted, sorted, and swirled around, creating value among collaborators irrespective of whether they congeal into a prose artefact.

That's not to say that polished prose isn't valuable; it's that school tends to overlook the value of fragments.

Teaching students to capture details

When I talk about fragments, I'm really talking about details unencumbered by any connective tissue. Details that are free to be combined and recombined in loose relationships.

We can teach students to get better at observing, capturing, and combining these kinds of details.

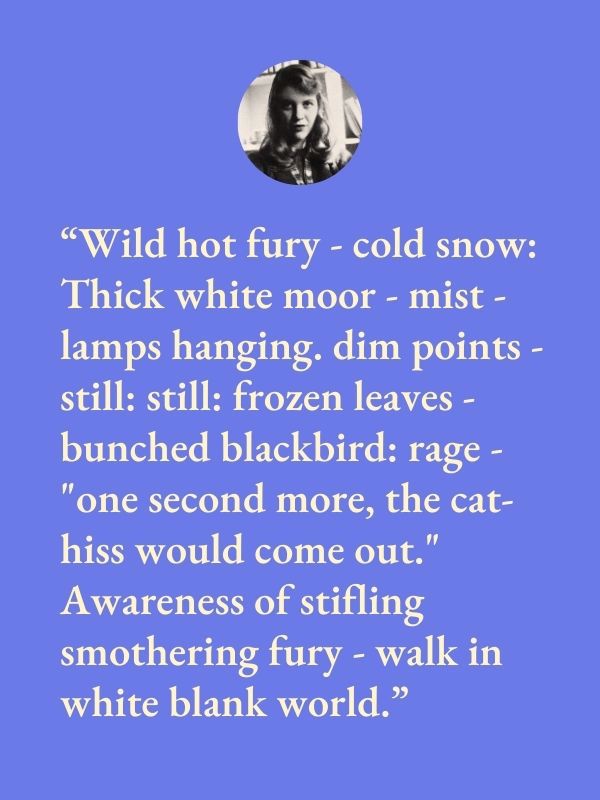

For example, one of my favourite game formats in Teaching Narrative Writing with Frankenstories uses each round to scaffold the players' observation and imagination:

- Collect obvious details from the image

- Zoom in and "observe" hidden details

- Zoom out and imagine details outside the frame

- Imagine details that deliberately break context

- Combine details to make interesting relationships

Here's an example of what that looks like in practice:

If you play this game format, you'll often find you have to actually stop players from writing stories.

And once your students have the hang of it, they can write lists of details in any game format.

There are great benefits to this:

- Reduce the cognitive load on struggling students.

- Develop a valuable skill.

- Build a foundation for more 'complete' writing.

Transitioning to 'proper' writing

Obviously, at some point students need to transition from fragments to connected prose.

Once you've got the details, you can scaffold approaches to connecting them through verbs, adverbs, prepositions, and other connectives—all of which you can approach in stages and layers.

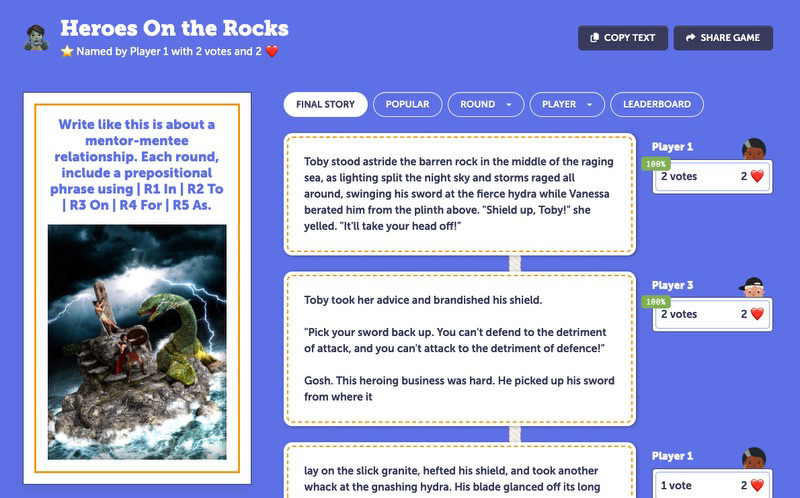

For example, in Frankenstories, you could play some of the grammar-based game formats, like this one that specifies a different preposition in each round:

Or you could use Writelike lessons and call out connective devices, or do something else entirely.

I could go on

I love this way of approaching things so much that I could go on for ages about observation, free association, combinatorial ideation and the process of drafting and revising a piece of work, but I'll stop there for now!

I hope this gives you some ideas for how you might use them strategically in Frankenstories games to support your students' writing.