THE SCARY TRUTH

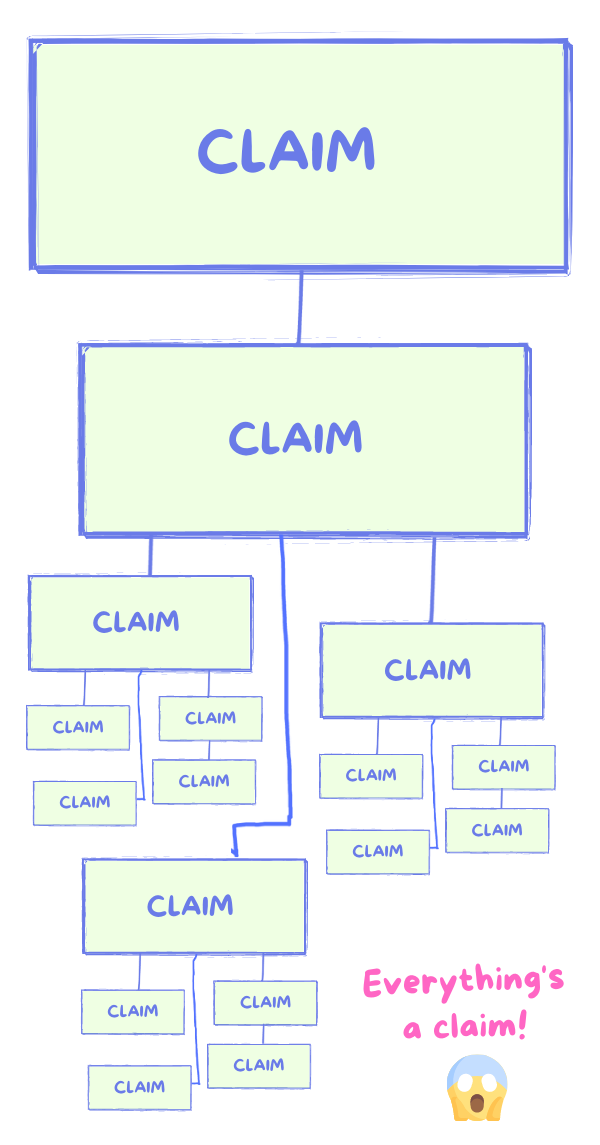

By this stage, we're building an increasingly elaborate architecture composed of issues, claims, reasons, and evidence (plus limits and rebuttal).

The existential crisis comes when you realise that all these components are, actually, just claims with fancy job titles.

Everything's a claim, because everything can be challenged.

"Evidence" is made of "facts", but facts are just claims that everyone already agrees on and take for granted.

Even the most elemental fact can be challenged. Not necessarily correctly or in good faith—but argument is a social process, and sometimes people will dispute even the most basic facts.

(This is why trust is fundamental to argumentation.)