If you want to hear some examples of contrast in music, consider these three pieces.

First, ambient music from Traßel SüD. This establishes a good baseline for what "low-contrast" music sounds like:

Filo by Traßel SüD Spotify | YouTube

You can hear that this is all soft, tonal, ambient music. There's a shape, but it's airy and spacious. If it contrasts with anything, it's the noise and brightness of the world outside.

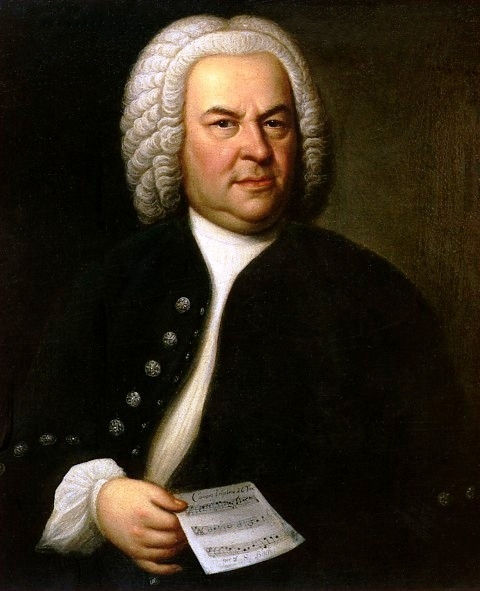

Next, an example of a classical piano piece that could be considered low or high-contrast, depending on how you look at it:

Partita No. 1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825: V. Minuetts I & II by Johann Sebastian Bach Spotify | Youtube

If you listen to this composition, you'll notice the dinky-dinky quality, and if you're not familiar it might sound like clockwork noise. But if you listen closely you'll find contrast in the way that melodic lines ascend and descend inside the loops.

In comparison, here is a contemporary pop-rock song that is relatively high-contrast:

Parasite Eve by Bring Me The Horizon Spotify | Youtube

If you listen to this song, you'll find it's full of deliberate and overt contrasts between volumes, timbres, and rhythms.